Easy Layout - a DSL for NSLayoutConstraint

Layout has changed in iOS 6. We no longer are supposed to calculate RectangleFs and set springs and struts (AutoresizingMask), we are to use this very advanced constraint solving system. I wrote a library to make writing constraint-based UIs easier.

That’s wonderful! Springs and struts, for those unfamiliar, is a lot like Anchors in Win Forms programming. It’s a really great model while you’re using an interactive design tool for layout, but if you want to do all your UI construction in code, then it’s a bit of work and relies on a lot of assumptions.

For example, here is the code to layout a simple screen with a text box and a button:

void LayoutWithSpringsAndStruts ()

{

var b = View.Bounds;

button.Frame = new RectangleF (

b.Width - HPadding - ButtonWidth,

VPadding,

ButtonWidth,

44);

button.AutoresizingMask =

UIViewAutoresizing.FlexibleLeftMargin |

UIViewAutoresizing.FlexibleBottomMargin;

text.Frame = new RectangleF (

HPadding,

VPadding,

b.Width - ButtonWidth - 3 * HPadding,

text.Font.PointSize + 14);

text.AutoresizingMask =

UIViewAutoresizing.FlexibleWidth |

UIViewAutoresizing.FlexibleBottomMargin;

}

This code is easy to write. You just imagine the UI in your head and write this function down as fast as possible. Why fast? Because this code is read-only. It defies modification. Imagine if there were 10 different views each with their own obnoxious RectangleF math.

There are also a lot of assumptions in the code. How tall should a button be? I don’t know so I just put in the constant 44. Likewise, how tall should the text field be? Who knows, but I found some math involving fonts that works decently well.

A better way

Apple must have gotten tired of writing this kind of code because they developed a wholy new layout system based on mathematical constraints.

In this new system you layout views relative to one another instead of using absolute coordinates, and you specify those relations using equations and inequalities:

View1.Property1 (== | <= | >=) View2.Property2 * mul + constant

That is to say, any layout property of a view can be constrained to be dependent on another property of another view. The power (and trouble) with this system derives from this generality.

Instead of positioning the text field using a RectangleF, I create a bunch of constraints:

button.Width = ButtonWidth

button.Right = View.Right - HPadding

button.Top = View.Top + VPadding

text.Left = View.Left + HPadding

text.Right = button.Left - HPadding

text.Top = button.Top

These 6 constraints lay out the UI in the same way as the springs and struts code above. But it is superior in a lot of way:

-

It makes no assumptions about sizes. When using the new layout systems, Views can control their minimum size. This means that I don’t have to guess at the two heights anymore.

-

There is no math involved. As much as I like measuring pixels and flexing my algebra skills, I am relieved to not have to do RectangleF math.

-

It’s easy enough to read this code that I would even feel confident editing it over time. That is to say, it’s not read-only code. While it’s still not easy to get a picture of the UI from these constraints, they are much easier to reason about than the prior pixel math.

But there’s an issue. I haven’t actually shown you the code you need to write to implement these constraints. Without further ado:

void LayoutWithConstraints ()

{

// Set button width

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

button, NSLayoutAttribute.Width,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

null, NSLayoutAttribute.NoAttribute,

0, ButtonWidth));

// Set button top

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

button, NSLayoutAttribute.Top,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

View, NSLayoutAttribute.Top,

1, VPadding));

// Set button right

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

button, NSLayoutAttribute.Right,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

View, NSLayoutAttribute.Right,

1, -HPadding));

// Set text left

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

text, NSLayoutAttribute.Left,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

View, NSLayoutAttribute.Left,

1, HPadding));

// Set text right

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

text, NSLayoutAttribute.Right,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

button, NSLayoutAttribute.Left,

1, -HPadding));

// Set text top

View.AddConstraint (NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

text, NSLayoutAttribute.Top,

NSLayoutRelation.Equal,

button, NSLayoutAttribute.Top,

1, 0));

}

Our 6 constraints have inflated to 30 lines of code. Frown face. You can imagine how beautiful this code is in Objective-C where you’re forced to name every argument…

Apple likes verbose APIs, but even they had to admit that this code is a bit ridiculous. So much so that they invented this THC-induced ASCII art way to establish these constraints. We will avoid this topic.

So we’re stuck in an awkward place:

- We can keep using springs and struts and pretend that the world hasn’t moved on.

- We can write constraints using ridiculous amounts of code.

- We can draw ASCII art and songs about California while we’re at it.

Challenge Accepted

The world can always be improved. There is no reason to be stuck with these 3 bad options when we use a fantastically powerful language (dearest C# 5, this is a love letter) with a runtime that will keep us safe during our adventures.

We are actually going to take our queue from Apple’s THC language, but let’s develop a DSL that’s easier to understand and aligns better with the actual constraints themselves.

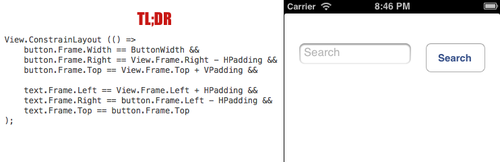

Here is what I came up with:

void LayoutWithEase ()

{

View.ConstrainLayout (() =>

button.Frame.Width == ButtonWidth &&

button.Frame.Right == View.Frame.Right - HPadding &&

button.Frame.Top == View.Frame.Top + VPadding &&

text.Frame.Left == View.Frame.Left + HPadding &&

text.Frame.Right == button.Frame.Left - HPadding &&

text.Frame.Top == button.Frame.Top

);

}

If you squint, this code is identical to the 6 constraint equations written earlier. I had to swap == in place of = and I had to put .Frame everywhere because this code needs to compile. But, overall, this DSL quite perfectly matches the constraint system itself.

When this code finishes, the View will have 6 new constraints added to to it. Let’s take a look at them using View.Constraints:

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xc55c9f0 H:[UIRoundedRectButton:0xc524180(88)]>

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xb4b2830 UIRoundedRectButton:0xc524180.right == UIView:0xc52c4e0.right - 22>

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xb4b0e70 V:|-(44)-[UIRoundedRectButton:0xc524180] (Names: '|':UIView:0xc52c4e0 )>

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xb4b2110 H:|-(22)-[UITextField:0xc52a710](LTR) (Names: '|':UIView:0xc52c4e0 )>

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xb4b20a0 UITextField:0xc52a710.right == UIRoundedRectButton:0xc524180.left - 22>

<NSLayoutConstraint:0xb4b2200 UITextField:0xc52a710.top == UIRoundedRectButton:0xc524180.top>

If you are one with the Visual Format Language, then you can see that our constraint equations turned into NSLayoutConstraints appropriately.

So there you go, Option #4: Easy layout. This code is shorter than springs and struts, has all the power of auto layout, and is a lot easier to read and write than both.

How it Works

In order to provide this layout DSL, I took advantage of Linq expressions:

public static void ConstrainLayout (this UIView view, Expression<Func<bool>> constraints)

When we pass code of the form () => button.Frame.Width == ButtonWidth to ConstrainLayout, the compiler does two things:

- It compiles the code and statically checks types just as you would expect.

- The compiler does not execute the function, nor does it pass it to

ConstrainLayout; instead, it gives you the abstract syntax tree of the function represented using theExpressionhierarchy.

What we do with those expressions after compilation is up to us. This is the true power of Linq. While from x in xs syntax is cool, I think this ability to do metaprogramming is 1,618 times more cool.

Since we can do anything with expressions, let’s turn them into NSLayoutConstraints! Here’s the driver:

public static void ConstrainLayout (this UIView view, Expression<Func<bool>> constraints)

{

var exprs = new List<BinaryExpression> ();

FindConstraints (((LambdaExpression)constraints).Body, exprs);

view.AddConstraints (exprs.Select (CompileConstraint).ToArray ());

}

This code takes expressions of the form a && b && c and turns them into a list of expressions [a, b, c]. It then compiles each of those expressions into an NSLayoutConstraint and adds those constraints to the view. Easy.

A little more work is required to actually compile:

static NSLayoutConstraint CompileConstraint (BinaryExpression expr)

{

var rel = NSLayoutRelation.Equal;

switch (expr.NodeType) {

case ExpressionType.Equal:

rel = NSLayoutRelation.Equal;

break;

case ExpressionType.LessThanOrEqual:

rel = NSLayoutRelation.LessThanOrEqual;

break;

case ExpressionType.GreaterThanOrEqual:

rel = NSLayoutRelation.GreaterThanOrEqual;

break;

default:

throw new NotSupportedException ("Not a valid relationship for a constrain.");

}

var left = GetViewAndAttribute (expr.Left);

left.Item1.TranslatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = false;

var right = GetRight (expr.Right);

if (right.Item1 != null) {

right.Item1.TranslatesAutoresizingMaskIntoConstraints = false;

}

return NSLayoutConstraint.Create (

left.Item1, left.Item2,

rel,

right.Item1, right.Item2,

right.Item3, right.Item4);

}

This code implements all possible ways to specify constraints. Specifically, it can handle expressions of the form:

text.Frame.Width >= button.Frame.Width * 0.5f + 5;

text.Frame.Width <= View.Frame.Width;

button.Frame.Height == button.Height - 10;

And so on. In total, it takes 200loc to implement the layout DSL. You can see it on github.

These 200 lines of code will save me from writing 4 boilerplate lines of code per constraint. This is a real win. That’s 80% less code to write. #winning

Thanks as always to C# for making my life more pleasant, and the folks at Xamarin who let me use my favorite language on my favorite platform.