C# Code Prediction with a Neural Network

TL;DR I used Python to create a neural network that implements an F# function to predict C# code. The network was compiled to a CoreML model and runs on iOS to be used in my app Continuous to provide keyboard suggestions.

The Problem

My .NET IDE Continuous runs on iOS instead of the normal desktop environments programmers are used to. This isn’t so much a problem since mobile devices have plenty of horsepower these days, but it does present a few human interface challenges - the biggest of these is entering code.

My desktop computer features a 108 key keyboard while the iPad’s on-screen keyboard features 36 keys - quite a difference! You can also get hardware keyboards for the iPad that feature 64 keys - still quite a ways from 108.

To ease the problem of code entry, Continuous has always shipped with a “keyboard accessory” that gives access to lots of missing characters used while programming.

I made this list of keys by scanning a bunch of code and seeing the most popular characters used. I sorted that list by popularity and added some order to it so it wouldn’t seem too random to users.

This was a good start but I was never happy with it - my biggest complaint was that it had no awareness of context and would always show the same list. This meant you usually had to scroll it a bit to find what you want. It also didn’t help you with keywords and multi-character tokens such as =>.

I wanted a new suggestion engine that tried to guess what you intend to type next in order to ease coding.

A Neural Solution

I’ve spent the last year deep diving into neural networks and machine learning in general. I find it be a refreshing alternative to the rigid confines of programming while also being a whole new and unexplored solution space to wander around in.

I’m not the only one enchanted by this new tech - Apple has pushed ML forward with its CoreML library that ties to its hardware promising efficient execution. It’s liberating to know that my mobile devices are now powerful enough to run very sophisticated networks. This also means that I have an easy path to create networks and write apps that use them - it’s an exciting time!

The decision to use a neural network to solve my code prediction problem was an easy one given all of this. Now I just need to choose what kind of network to use.

Sequence prediction is a classic problem in neural networks these days. The idea is that if you learn patterns in a sequence, then you can start predicting that sequences (extrapolating). Sequences can be letters of a natural language, samples of audio, stock values (just kidding, don’t go down that dark path), or, hmm, bits of code.

The current favorite network architecture to use for sequence prediction is a Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). These puppies are special because they have an intrinsic understanding of a sequence of events made available by an internal memory. Most neural networks are strictly “feed-forward” - data goes in one end and comes out the other. In RNNs, however, have internal feedback - data comes in one end and can get captured by the memory of the RNN. This memorized data can then be used by the next prediction. It’s quite sophisticated, and with enough horsepower, can do amazing things.

So I have a well defined problem, and I even have a solution. Now I just need to code all that up.

Training Grounds

Neural network libraries are a dime a dozen these days. The trouble is that they all use different languages, slightly different vocabulary, different file formats, run on specialized hardware, and only feature the barest of documentation. It’s exciting! To add to the mix, every cloud vendor seems eager to sell off time on their expensive GPUs. Using these vendors requires learning their own proprietary ways of executing NN libraries and fun mix of APIs. They are usually cheaper than going out and buying hardware, but it’s exhausting…

To that end, I took a very conservative approach to building my network. I decided to use:

- Python as the programming language

- Keras as my high-level NN library

- PlaidML as the execution engine for training

- Training on local hardware (iMac Pro with an AMD Radeon Pro Vega 56)

I’ve used Python on and off throughout my career and am comfortable with it. But everyone who knows me is probably asking why I didn’t use C# or F# - my preferred application development languages. Quite simply, there are no .NET libraries that can take advantage of Mac hardware. Most of the .NET libraries are either CPU bound (nope, not even bothering) or only run accelerated on Windows (inconvenient for me).

The other reason to use Python is that it is what the rest of the NN community uses. This stuff is hard and I’m constantly googling. Translating from Python to C# is exhausting and, from an engineering perspective, pointless. That said, I do hope .NET NN libraries mature and they will be a viable option in the future.

Keras is a nice high-level API for constructing and training networks. It’s “high-level” because it abstracts the execution engine from the model definition and because it’s API is very readable. Also, the author of the library, François Chollet, has written a book called Deep Learning with Python that I absolutely adore. He gives clear explanations and lots of examples of lots of different types of networks. Normally Kera uses Tensorflow as its engine, but I’m not using that. Instead, I use OpenCL through PlaidML.

And now a shoutout for PlaidML - this shit is hot. Most NN libraries specialize for NVIDIA hardware (through Tensorflow). This monopoly is gross and quite burdensome to Mac users and anyone else not using NVIDIA devices. Not long ago, there were no hardware accelerated NN libraries for Macs…

Today, Apple is doing well on the model execution front, but has only made small inroads on model training.

Enter PlaidML. The library enables you to code standard Keras networks and train using a variety of hardware. It enables you to accelerate training and prediction on Macs, and I’m in love with it. If you’re a Mac or Windows user and don’t conform to the NVIDIA hegemony, then I suggest you give it a look.

Training Data

So just how do you predict what code comes next? It’s not a trivial problem and I think that there are a lot of ways you could present this problem to a NN.

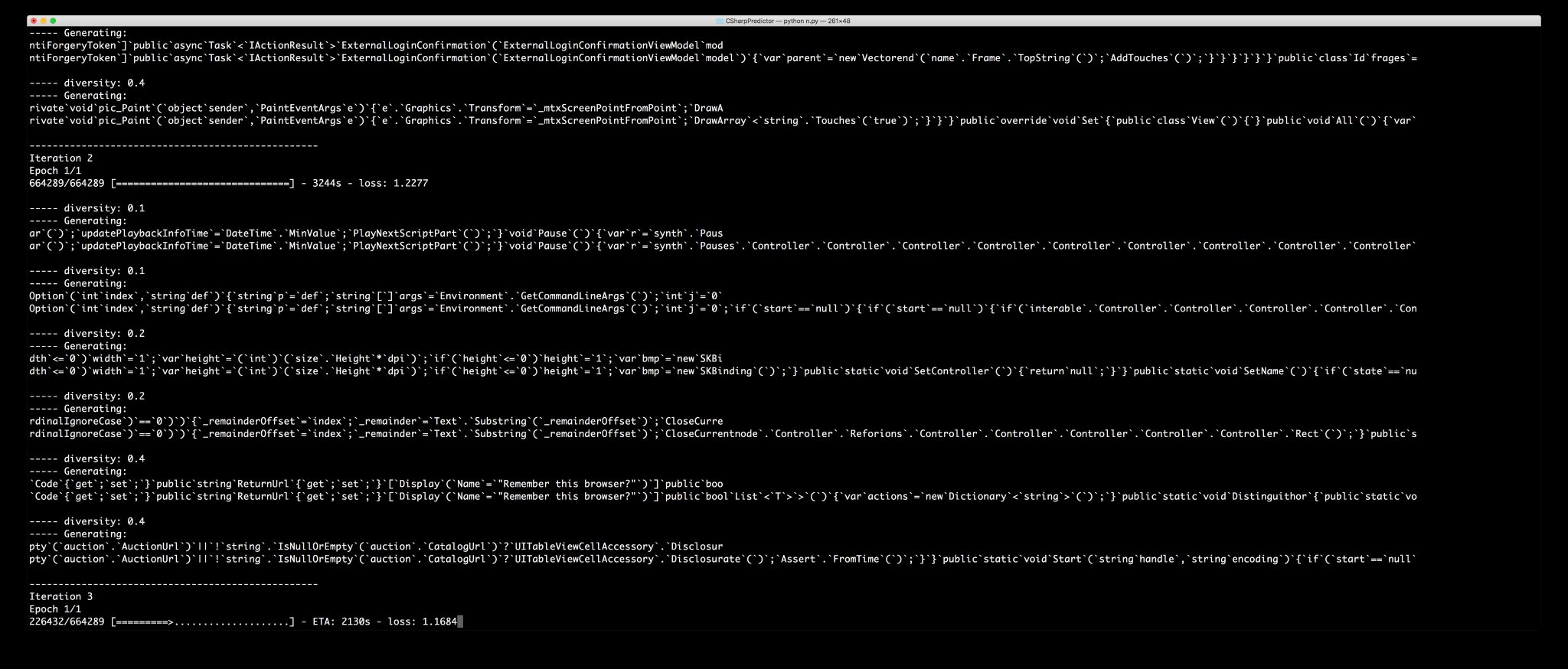

When I first worked on this problem, I did everything at the character level. I just fed the network code file after code file and told it: learn C#. Here is some of the silly code it generated:

https://twitter.com/praeclarum/status/985575617310539776

It’s fun to see it hallucinating variable names and data structures. But there were a couple problems with this network:

- It needed a pretty big history to do its job well - the version above used 80 preceding characters to make its prediction. When running on device, you have to execute the network for each history point and therefore execution speed is proportional to the amount of history. While CoreML is fast, this is asking a bit much in 2018.

- The network is quite big. Because it has to learn (1) the syntax of C#, (2) style rules, (3) variable and type naming rules, (4) even some semantics, the network had to grow and grow to do its job.

- It would generate doc comments that were nonsensical but still funny.

- It would get lost generating string literals. This is easy to work around but was a hilarious flaw. Learning all the things that we put in our strings really taxed this network. This was also a problem for numbers and any other literals.

- It was heavily biased towards my style of coding :-) It would use my kind of variable names, my whitespace formatting (honestly it could never choose between tabs and spaces either), and my libraries.

I decided that I’m asking a bit too much out of the net and that I would greatly simplify its task. This would result in a smaller model that I could more confidently train and was slightly less biased.

I decided to switch to “token types” as an item in a training sequence. I used Roslyn’s CSharpSyntaxTree to parse thousands of files and create sequences of token types.

Such a stream looks something like this:

UsingKeyword IdentifierToken SemicolonToken NamespaceKeyword IdentifierToken

OpenBraceToken PublicKeyword ClassKeyword IdentifierToken OpenBraceToken

PublicKeyword VoidKeyword IdentifierToken OpenParenToken CloseParenToken

OpenBraceToken CloseBraceToken CloseBraceToken CloseBraceToken ...

This corresponds with the code:

using X; namespace X { public class X { public void X() {} } }

As you can see it loses the concept of whitespace, loses all knowledge of variable names (identifiers), and doesn’t learn literals - it’s quite dumb in fact. It is still however learning the syntax of C# and common patterns that developers use.

While dumb, this is exactly the data that my keyboard wants and I decided that this is the training data that would be used by the network.

In all, I generated a sequence of 1,000,000 tokens for training and validation. There are about 150 different types of tokens that it will have to learn.

Do I Even Need a Network?

You might stop and wonder (as I did) that if I simplified the training set so much, do I even need a neural network? Wouldn’t a lookup table be enough?

The final network I built uses a history of 8 tokens to decide what the next token will be. How large of a lookup table is this? There are 150 token types and the lookup is 8 of these meaning there are 150^8 permutations. That’s a lookup table of 256,289,062,500,000,000 entries. I guess a naive lookup table is out of the question…

Are there other techniques? Sure, XGBoost (a decision tree) is a popular alternative to neural networks. It does very well in competitions and provides a completely different look at the data.

Unfortunately, my ML knowledge is specialized at this point to nets, so I’m just going to stick with what I know.

Building and Training

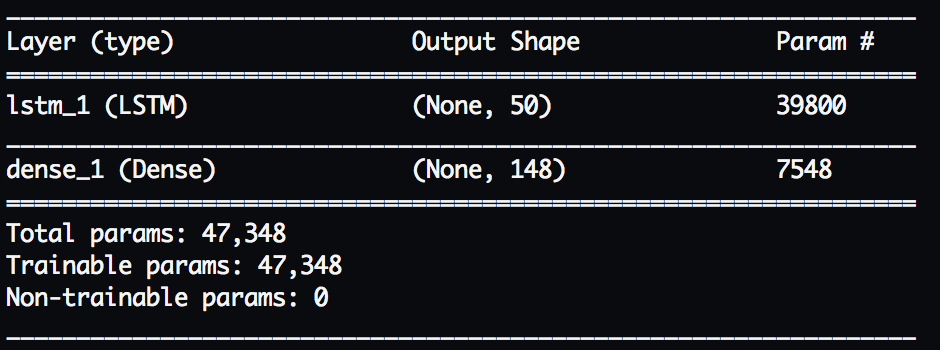

I constructed the most basic RNN I could use a single layer of LSTM (special nodes with the memory mentioned above) to learn patterns in the data and a final fully connected layer (Dense) to do the actual prediction of the next token.

Even with such a simple architecture, there are a lot of knobs to turn in order to train the net well. These are referred to as “hyperparameters”. For this model, they include:

- The amount of history to provide the network per prediction

- The number of nodes to use in the recurrent layer

- The types of nodes to use in the recurrent layer (LSTM, GRU, Conv1D)

- The activation functions of the layers

- How much data is provided per training session (epoch)

- How many epochs to train for

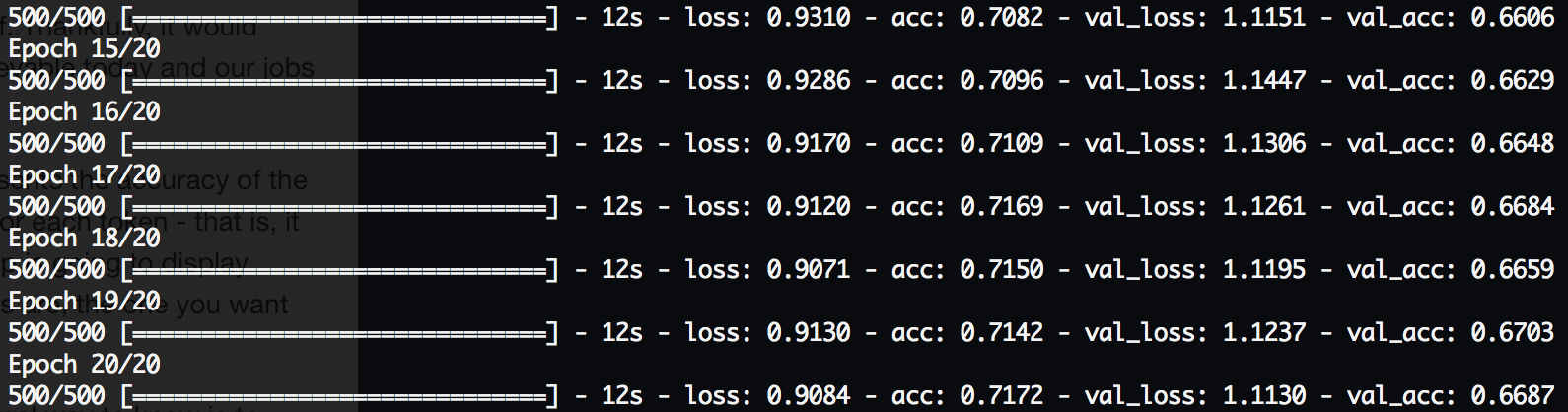

If I was a good engineer, I would write a script that varied these hyperparameters, automatically trained nets, and eventually reported to me the best combination. Instead, I tweaked them by hand until I found a good combination/was exhausted.

While training, you’re also balancing the size (and therefore speed) of the network vs its capabilities or accuracy. As this is my first network that I plan on shipping in an app, I wanted to stay conservative and tried to stay below 200 KB total model size.

In the end I trained a network with 67% accuracy and that required 8 history samples to make its prediction (using 16 samples only got it up to 69%). Here’s its summary:

What does 67% accuracy mean? Is it good?

The answer is, I don’t really know. :-) All I can say for sure was that it’s about as good as I could get this network (and those similar to it) to perform.

Let’s take a guess at what it means by considering some other accuracies. If we randomly guess the next token then we have a 1/150 chance that we’re right, or 0.7% accuracy. OK, so we’re better than random.

What would 100% accuracy mean? Well, I kinda think it would mean we’re out of jobs. If it correctly guesses every next token then that’s darn close to solving the original program’s problem and being a coder itself. Thankfully, it would have to understand so much that I don’t think it’s achievable today and our jobs are safe.

One other thing to consider is that this accuracy represents the accuracy of the net’s best guess. But, the net calculates a probability for each token - that is, it makes a second best guess, a third, and so on. My app is going to display these guesses along with the best guess, and, chances are, the one you want will be in that list.

So is 67% good? Eh, it’s not bad! But I think the only real way to know is to interact with it and use our own judgements.

Integration into an App

To use the trained model on iOS, it first needs to be converted to a CoreML model file. Apple makes this easy by providing a Python package called coremltools to convert from Keras models to their own. This produces a file called, in my case, CSharpPredictor.mlmodel

My IDE is written in F# using Xamarin. Xamarin has excellent support for importing models into C# projects, but things are a bit rougher in F# and a bit of extra code needs to be written. That extra code involves loading the model file and then compiling it to prepare it for use.

I created a function with a simple interface to act as the entry point, or bridge, to the neural network:

predictNextToken: SyntaxKind[] -> (SyntaxKind * float)[]

This means that it’s a function that takes an array of SyntaxKinds (what I keep calling tokens) and produces and array of guesses and their probability. (The actual code also returns other data needed by the IDE.)

/// Given previous tokens, predict the next token (and runners up)

let predictNextToken (previousKinds : SyntaxKind[]) : Prediction[] =

if ios11 then

let model : MLModel = model.Value // Load the cached model

let mutable predictions : Prediction[] = [| |]

// RNNs require external memory

let mutable lstm_1_h : MLMultiArray = null

let mutable lstm_1_c : MLMultiArray = null

// Run the model for each previous token

let inputKeys1 = [| s_prevVectorizedToken |]

let inputKeys3 = [| s_prevVectorizedToken; s_lstm_1_h_in; s_lstm_1_c_in |]

let mutable error : NSError = null

for kindIndex, prevKind in previousKinds |> Array.indexed do

// Convert the token to a vector for the model

let vectorizedToken = CSharpPredictor.kindToVector prevKind

// The first run doesn't include the memory

let inputKeys, inputValues = if lstm_1_h <> null then inputKeys3, [| vectorizedToken :> NSObject; lstm_1_h :> NSObject; lstm_1_c :> NSObject |]

else inputKeys1, [| vectorizedToken :> NSObject |]

let inputDict = NSDictionary<NSString, NSObject>.FromObjectsAndKeys (inputValues, inputKeys, System.nint inputKeys.Length)

let inputFeatures = new MLDictionaryFeatureProvider (inputDict, &error)

// Run the prediction

match model.GetPrediction (inputFeatures) with

| _, error when error <> null ->

Debug.WriteLine (error)

failwith "Prediction failed"

| output, _ ->

lstm_1_h <- output.GetFeatureValue("lstm_1_h_out").MultiArrayValue

lstm_1_c <- output.GetFeatureValue("lstm_1_c_out").MultiArrayValue

// If this is the last prediction, store the results

if kindIndex = previousKinds.Length - 1 then

predictions <-

output.GetFeatureValue("nextTokenProbabilities").DictionaryValue

:> Collections.Generic.IDictionary<NSObject, NSNumber>

|> Seq.map (fun (x : System.Collections.Generic.KeyValuePair<NSObject, NSNumber>) -> string x.Key, x.Value.DoubleValue)

|> Seq.filter (fun (_, p) -> p > 1.0e-4)

|> Seq.sortBy (fun (_, p) -> -p)

|> Seq.map (fun (tokenName, p) ->

let kind = CSharpPredictor.stringToSyntaxKind tokenName

let insertText, formatText = CSharpPredictor.kindToCompletion kind

kind, insertText, formatText, p)

|> Array.ofSeq

predictions

else

[| |]

The code is a little long winded because it needs to manage the memory of the RNN and because I need to play games with NSDictionary due to the missing binding (in C#, this code would be cleaner).

This code also filters out any guesses with a probability less than 0.0001 just to throw away the predictions that are very unlikely. The list actually gets decreased further in the UI code.

An important but easy part to miss in the above code is when it converts the token to a vector that’s usable by the model (the function CSharpPredictor.kindToVector). Neural networks don’t understand categorical data natively so we convert each one to a “one hot vector” which is terrible binary encoding that these things love. In order to keep the network in sync with my code data types, I generate a code file that contains this mapping from SyntaxKinds to MLMultiArray along mappings to the literal text to insert.

Every neural network you build is going to need a wrapper function like this - something that bridges the gap from the bytes and datatype traditional programming world to the dataflow connectionist world of neural networks. The complexity of the function depends on how similar your inputs and outputs of the model match the inputs and outputs of the program. In this case, it was a pretty easy function to write.

Putting it all Together

I now have a trained network, and I have code to execute it. The last step is to wire it into the UI so I can finally interact with it.

This was pretty easy given how the IDE works. Whenever the user edits text, the document gets parsed by Roslyn. The app then takes the current cursor position and scans the syntax tree backwards collecting previous tokens. Those tokens get passed to the predictNextToken function above to produce the ranked predictions. (This all happens on background threads to keep the UI snappy.)

Those predictions are passed to the keyboard accessory which is just a UICollectionView. And that’s that; as you move the cursor around, the predictions appear above the keyboard.

Keep an eye on the black bar above the keyboard and note how it changes based on the cursor position. It’s not perfect, but its top couple matches are usually right.

Future Improvements

For now, I kept the code completion window separate from this predictor but I can imagine fusing them at some point. In early versions I did present the predictions in the floating window, but that got obnoxious.

There’s certainly room for the network to grow. I am considering change the inputs yet again to see if I can get decent variable name prediction. Right now, when the network detects with 99% certainty that you need to enter a name, then it should make some guesses. I would also like to add back in some whitespace support - for example, knowing when to start a new line - but then it’s making stylistic decisions.

I am also playing with giving the network more context to work with. I can use Roslyn’s syntax tree to provide the network with a lot of direct context that it won’t need to learn on its own. This should simplify the network and make it more accurate.

In all, I think that there are a lot of ways to improve this and make little neural assistant programmers a possibility. But for now, I just love seeing it say “you really want to put an if statement here”.