Containing Null with C# 8 Nullable References

C# 8’s nullable reference types are designed to help rid your apps of the dreaded NullReferenceException. This article walks you through the common errors that you will encounter while updating your app and offers a few of my opinions on how to fix them. It’s a long and windy road to update to nullable references, but you will come out at the end more confident in your code and with fewer bugs.

I use Microsoft’s AppCenter to collect crashes from my apps and it’s a humbling experience. You think you’re smart

and you think that you really have a grip on this programming thing - and then you see it - NullReferenceException - the most embarrassing of all the bugs.

When I was a young programmer, my apps would crash with Access Violations on Windows. That was the OS telling me I’m a bad programmer. Later in my career, the OS would tell me with SIGSEGV and core dumps on Unix.

Then C# came around with its amazing managed memory. This technology had the promise of forever preventing silly memory errors such as these, and for the most part, it did:

- We could no longer access unallocated objects.

- We no longer had to worry about someone freeing our objects.

- We no longer could randomly poke around in object’s memory and corrupt them.

That all sounds super safe, but there was a deficiency. The designers decided that null objects were still a valuable concept and deserved

to be representable. We programmers, still believing that we were smart, gleefully agreed that null is useful,

and sure, why not, let’s let every object be nullable.

For all of C#’s life, we had mostly safe memory access, but my old friends Access Violation and SIGSEGV could still come crashing the party. They wore “NullReferenceException” shirts, but I recognized them from under their disguises.

For me, personally, that all changed when I started programming F#. The F# designers shared my hatred of stupid memory errors and decided that null just wasn’t worth it. The F# language does all it can to convince your not to use null and your programs benefit from it tremendously.

It took 8 versions, but the C# designers have come around and decided to help programmers with this one last memory mistake. I have been excited for this enhancement for years and am overjoyed to finally be able to use it.

Updating an app to C# 8.0

Since Connect 2018, I have been converting projects (so far, SolidGeometry and CLanguage) to use the new nullable references feature.

Doing so for your projects involves three easy steps:

- Install .NET Core 3.0 which includes C# 8.

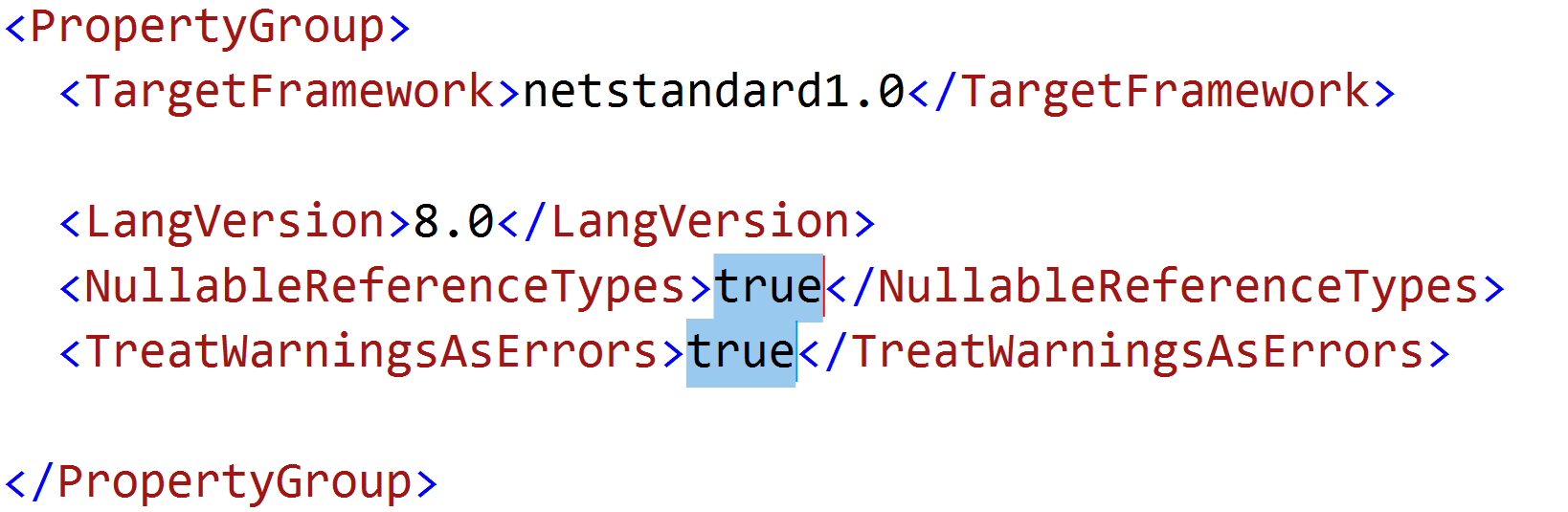

- Set the language version to 8.0:

<LangVersion>8.0</LangVersion>to your .csproj file. - Add the property

<NullableReferenceTypes>true</NullableReferenceTypes>.

Adding that property will change the behavior of the compiler in these ways:

- It will track your usage of null using data-flow analysis

- It will now assume that null is not allowed on any objects (a proper default!)

- If you want to use null, you will have to explicitly declare variables and fields as nullable.

- It will signal inconsistent uses of null

While converting the project is easy, you will now receive a variety of errors from the compiler. Working through these will take some time, but the effort is worth it.

There are lots of warnings C# 8.0 with Nullable Reference Types can generate. You can see them in the Roslyn source code. The remainder of this article will be an exploration of these errors and how I go about fixing them.

Put a “?” wherever you use null

The first step to converting an app to use nullable reference types is to annotate types that are known to be nullable with ?. The compiler helps you track them down with these errors:

🔴 error CS8625: Cannot convert null literal to non-nullable reference or unconstrained type parameter.

This is the starting point for introducing nullability into your code. The compiler is saying that

you have declared something as not-null, but you went ahead and literally assigned null to it.

This usually means you haven’t completed annotating your code yet. If you used

an explicit (literal) null, then you need to declare that variable as nullable:

string name = null; // ERROR! CS8625

In this code, I have declared name to be non-nullable and yet I put a null right there in the code.

The fix is to make it nullable by adding a ? to its type:

string? name = null; // OK!

Now that we have declared our intentions properly, the compiler will be happy and move on. If your code, later on, uses that variable without checking its nullness, you will start getting CS8602s.

🔴 error CS8600: Converting null literal or possible null value to non-nullable type.

This usually happens when you use var to create and initialize a local variable from a non-null reference but then

later in the code you set it to null.

Your code might look something like this:

var node = this; // Initialize non-nullable variable

while (node != null) {

if (ShouldStop(node))

node = null; // ERROR! CS8600

else

node = node.Next;

}

You can fix it to be:

Node? node = this; // Initialize nullable variable

while (node != null) {

if (ShouldStop(node))

node = null; // OK!

else

node = node.Next;

}

(Maybe someday, perhaps, we will get var?)

🔴 error CS8603: Possible null reference return.

You have declared that a method or a property will always return a value (non-null), but your code can, in fact, return nulls. A common case of this occurs with properties:

public class Person

{

public Address? Address { get; set; };

public string Country => Address?.Country; // ERROR! CS8603

}

Here, I have declared a property Country that always return a valid string object.

However, in my code for it, I use null propagation of a nullable value to return the result.

This means I can, in fact, return null values.

You can either re-write the function to never return nulls, or redeclare it. Re-writing the function is a tall order if you don’t understand the code base or don’t have good unit tests. In that case, re-declaring the result as nullable is your safest bet:

public class Person

{

public Address? Address { get; set; };

public string? Country => Address?.Country; // OK!

}

Initialize your data types

If your fields in your data objects are non-nullable (require values), then you will have to make sure to initialize all of those fields in the object’s constructor. These errors will help you:

🔴 error CS8618: Non-nullable property ‘Name’ is uninitialized.

This happens when you have declared that a field or a property requires a value (because its type doesn’t have a ?), but you did not initialize that field in a constructor.

For example:

public class Person

{

public string Name { get; set; } // ERROR! CS8618

}

The compiler is upset because you said the Name cannot be null, but, by default, fields and properties of objects are initialized to null. Conundrum!

There are a couple of ways to fix this. Which one you use will depend on how you use that object and those fields in your code.

If your code is designed to handle that field being null, then by all means just annotate it as such:

public class Person

{

public string? Name { get; set; }

}

This is the simplest fix but will produce new errors (CS8602s) in code that assumed it was non-null.

If you find that your code does assume that there is always a valid value and you don’t want to deal with a million new errors, then you had better initialize that puppy in a constructor:

public class Person

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public Person(string name) {

Name = name ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(name));

}

}

I’ve found, in general, object initialization expressions (new Person { Name = "Frank" })) need replacing with these kids of constructors.

Introducing a constructor like this will break all the code that relied on a default constructor and it’s going to be tedious work.

Whether you decide to put the throw new ArgumentNullException is up to you since the compiler will now do a good job of detecting bad arguments. I follow these rules:

- If the class and method are public and in a library, I do runtime checks for

null. This ensures that code not using C# 8.0 will still get errors if they pass nulls to your code. - In all other cases, I trust the compiler’s analysis and elide the checks. Perhaps there is some hubris to this decision, but I am so over runtime null checking.

What if you don’t want to create a constructor because it’s just a data object and you miss C++ and uninitialized memory? Well, my best advice is to still initialized these objects but use special objects that somehow still represent the concept of emptiness. We have a few of these in .NET:

String.EmptyArray.Empty<T>()Enumerable.Empty<T>()

These are great to initialize objects to ensure fields are not-null. Your code would become:

public class Person

{

public string Name { get; set; } = string.Empty;

// -or-

public string Name { get; set; } = "";

}

Now the object can be initialized without parameters and code can be written without worrying if Name is null.

If you have custom types then you will end up initializing those objects with default constructors:

public class Person

{

public Address Address { get; set; } = new Address();

}

There is a philosophical debate to be had as to whether you have just invented “another null” with these “empty” objects. On the pro side, you don’t have to deal with NullReferenceExceptions, on the con side, your code still has to deal with the concept of emptiness.

That is why I recommended marking uninitialized fields of data objects as nullable (string? in this case). While I hate nulls, I think re-inventing new classes of null is a worse crime. It’s better to deal with the compile-time errors that result than to make another billion dollar mistake.

Fix your bugs

With all your types annotated, and all your objects properly initialized, you will now encounter a variety of errors about your inconsistent use of null.

This is where the bugs are. This is what it has all been for. This is the compiler helping you rid your code of NullReferenceExceptions.

That said, this is the most tedious part of the process because it will make you question your own code and your own assumptions.

It will also expose tricky scenarios in which you will be convinced the object cannot be null but the compiler insists that it can be. It doesn’t matter who’s right, because you’re wrong. If your code is tricky enough that you can’t convince the compiler, then rewrite your code to be simpler and more obvious. Compilers and humans alike will thank you.

So… get some coffee… put on some melodic death metal, and get to fixing these errors.

🔴 error CS8602: Possible dereference of a null reference.

This is the biggest error that you will run into. It can either mean the compiler has found a bug in your code or you have done an insufficient job annotating your types. Gotta put your thinking cap on to find out which.

Let’s look at some examples.

Compiler knows more than you

I run into it when I “cleverly” check a variable for non-nullness and store the result in a variable:

class Person

{

public void SayHi() => Console.WriteLine($"Hi!");

}

Person? person = FindPerson();

var isPerson = person != null;

if (isPerson) {

person.SayHi(); // ERROR! CS8602

}

We can look at the code and reason that the method call is safe. The compiler, on the other hand, isn’t so sure.

These are tricky situations.

Sometimes, the compiler really does know something more than you. It might have noticed a mutating call somewhere. It might unravel some of your spaghetti logic and come to different conclusions than you.

For example I once had this code:

var person = new Person();

DoSomething(ref person);

person.SayHi(); // ERROR! CS8602

You can see my intentions; at first glance the code looks OK.

But, the compiler knows that DoSomething could really do anything

and assign person to be null. Smart.

I thought that person could not be null, but I was wrong and need to change my code to handle it.

Compiler knows less than you

Other times, the compiler just isn’t sophisticated enough.

Back to this example:

var isPerson = person != null;

if (isPerson) {

person.SayHi(); // ERROR! CS8602

}

We’re sure the code is safe, but how do we convince the compiler?

Putting the != null check right in the if statement works best:

if (person != null) {

person.SayHi(); // OK!

}

or you can use the null propagation operator:

person?.SayHi(); // OK!

Or maybe it’s a bug

CS8602 is probably the error you’ll run into when you discover a bug in your app. Congrats, you can now take one step closer to perfect software!

🔴 error CS8601: Possible null reference assignment

This error is raised when the compiler can’t tell if you checked a nullable value before assigning it to a non-nullable variable.

Just like with CS8602 this error can happen when you store the results of null checks in variables:

string? name = GetName();

var hasName = name != null;

if (hasName) {

string fullName = name; // ERROR! CS8601

}

We can reason that the assignment to fullName is safe, but, once again,

the compiler isn’t so sure.

Putting the != null check right in the if statement is usually best:

if (name != null) {

string fullName = name; // OK!

}

🔴 error CS8604: Possible null reference argument for parameter ‘person’ in ‘void Database.Insert(Person person)’

This occurs when a method has declared that its parameter is non-null, but you have passed a nullable value as the argument.

class Database

{

public static void Insert(Person person) {}

}

Person? FindPerson(string name) => null;

Database.Insert(FindPerson ("Frank")); // ERROR! CS8604

Here I have declared that inserting into the database requires a valid Person object.

However, I am actually passing a nullable value to the method.

This happens a lot and you have your normal choice of either re-declaring and re-implementing the method to accept null arguments, or you can make sure the value you pass to it is not null.

Run those unit tests!

In both projects, I managed to introduce a bug or two while trying to “fix” my inconsistent use of null. Thank goodness for unit tests!

My mistakes were usually overcorrections while trying to avoid null. For example,

-

Early return when null Sometimes I would add a line like

if (x == null) return;while not realizing that the code below does actually want nulls to the algorithm to be correct. -

Caching non-null values I get a little tired of writing

if (x.Foo.Bar.Baz != null) ...and cache the result in a local variable:var baz = x.Foo.Bar.Baz. This cache should be invalidated if eitherx, orFoo, orBar, orBazmutates, but sometimes I forget to. (I wish C# supported first-class data binding.) -

Reflection The compiler cannot understand any games you play with reflection. Also, nullable references are only a C# concept and are not supported by the CLR. This means that you can use reflection to undermine all of the nullable rules. So, um, don’t do that.