I Built the World's Largest Translated Cuneiform Corpus using AI

TL;DR I used a custom-trained Large Language Model (T5) to create the world’s largest online corpus of translated cuneiform texts. It’s called the AICC (AI Cuneiform Corpus) and contains 130,000 AI translated texts from the CDLI and ORACC projects.

Cuneiform

Cuneiform is the oldest known writing system. It was used in Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) for over 3,000 years. It was used to write Sumerian, Akkadian, and other languages. Written on clay, it has survived the millennia and is now being translated by scholars around the world.

Sadly, we have more clay tablets than scholars. Fortunately, we have computers.

Introducing the AICC

I’m proud to introduce the AICC - a collection of 130,000 cuneiform texts translated from ancient Sumerian and Akkadian to English using a neural network. It is the largest collection of translated cuneiform texts in the world.

This is the 2nd edition of the translated corpus I released last summer. The 1st edition contained about 30,000 texts but this new edition boasts 130,000 texts. The corpus is growing fast!

How good are the translations? Well, they’re decent. :-) I hope you’ll go browse the site and see for yourself.

Judging the quality of cuneiform translations has a rich history. Indulge me in a story.

Can it Translate Tiglath-Pileser?

In 1857 a new cylinder inscribed with cuneiform text and the name Tiglath-Pileser was found (dated 1150 BC). At this time, cuneiform was just being relearned and there was a question as to how good various translation methods were.

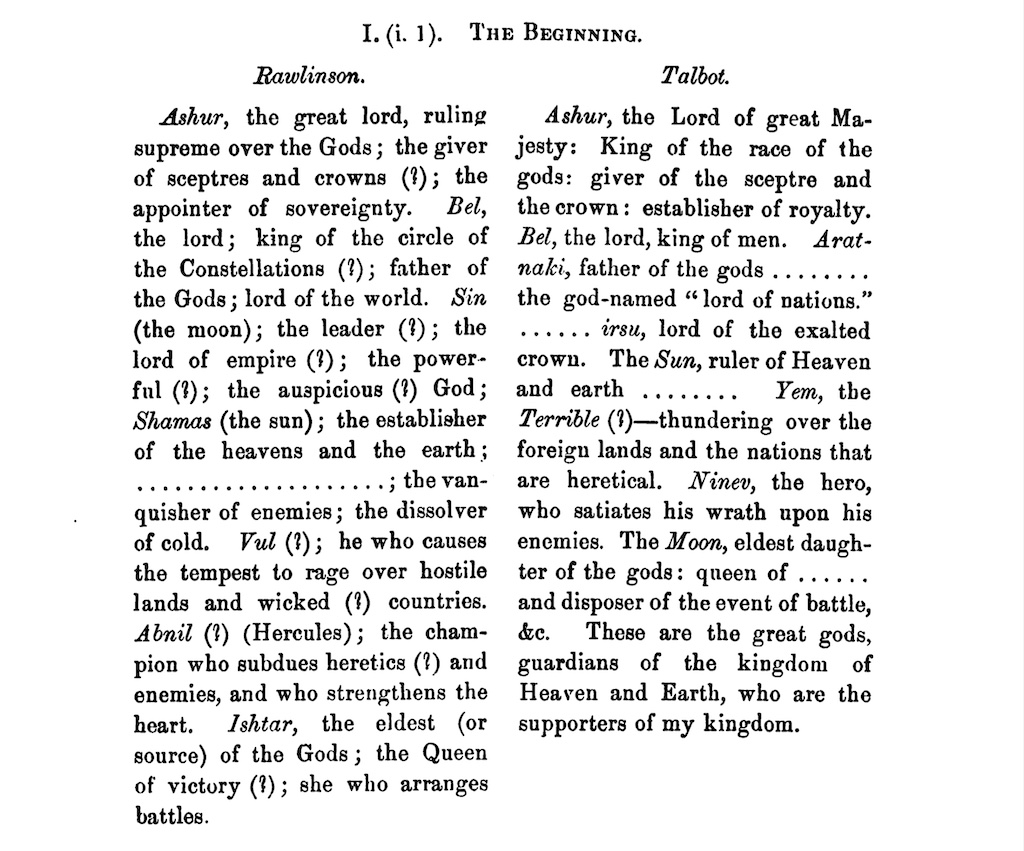

The Royal Asiatic Society decided to perform an experiment (that was later published as the book Inscription of Tiglath Pilser I., King of Assyria). They would give the same inscription to three different translators and see how well they did. The idea was that if the translations were similar, then the current understanding of cuneiform was also good.

Here is a page from the book showing the beginning of two of the three translations:

We can see that although the translations are different, they convey the same meaning. The experiment was a success.

I am pleased to now add my own (well, my AI’s) translation to the mix. Just one problem, my corpus contains many objects with similar inscriptions and I’m not sure which one is this specific Tiglath-Pileser cylinder. There’s P393923, P463064 (newly translated), P463510 (newly translated), P467316 (newly translated), Q005926, Q006021 and more.

I decided in fairness and in the spirit of the competition to translate one that had no previous translation. I chose P467316 as its beginning seemed to match the other translations.

AI Translation of Tiglath-Pileser

AI Translation.

Ashur, great lord, who makes the totality of the gods submit, who gives scepter and crown, who establishes kingship; Enlil, lord, king of all the Anunnaku gods, father of the gods, lord of the lands; Sin, wise one, lord of the crown, saqu-worthy; Magur, Shamash, judge of heaven and underworld, who carries out the slander of the enemy, who breaks up the foe; Adad, hero, conqueror of the four quarters of the lands, the four quarters; Ninurta, hero, villainous sacrificial spirit and enemy, who destroys the heart of the people; Ishtar, foremost among the gods, lady of battle;

The great gods, who make the heavens and earth a lordly place, whose utterances are a scepter and a scepter, who make kingship supreme, Tiglath-Pileser, beloved prince, your beloved, your shepherd, who by your true heart you have entrusted to me, this exalted one, you have established for the sovereignty of the land of the great Enlil, you have granted him a scepter.

Continued in P467316.

While stilted in places, it is a decent translation, and I deem this experiment a success!

Why AI Translations?

Existing online repositories (CDLI, Oracc) contain many transliterations of ancient cuneiform texts (a transliteration is a rewriting of a text from one writing system to another without changing the language), but they are very lacking in the translations department.

While I am not a cuneiform expert, I am an expert at neural networks and have a deep passion for languages and writing systems. I want any person to have access to the archives of the ancients. A grandiose goal for sure, but also a very achievable one thanks to modern engineering advancements.

Sumerian

Consider Sumerian (spoken by the creators of cuneiform). There are currently 103,075 texts published with transliterations from cuneiform symbols to (mostly) latin letters. But only 4,583 of these texts have publicly available translations online. That is a mere 4% of texts available to a lay person such as myself.

| Publications | Count |

|---|---|

| Transliterated | 103,075 |

| Translated | 4,583 |

| Need Translations | 98,492 |

Given the existing transliterations, there are 98,492 works that can be translated but have not yet been.

(There are more translations than these, but the others are not freely available and are held under copyright. In other words, you need to go by a book to read them.)

Things aren’t much better for Akkadian (the language spoken by the famous Sargon and Ashurbanipal).

Akkadian

| Publications | Count |

|---|---|

| Transliterated | 31,747 |

| Translated | 10,069 |

| Need Translations | 21,678 |

We can see that 21,678 works are all set to be translated but have not been.

Training a Large Language Model

The modern advancement of large language models (LLMs) has affected and will continue to affect nearly every human endeavor.

The current architecture that is heralding this new age of knowledge is the Transformer architecture. It was designed specifically to be very good at translating text from one language to another using the innovative “attention mechanism”. It’s a little funny that this network designed for translation is now broaching the realm of artificial general intelligence (AGI), but I digress.

Ignoring the absurdly large LLMs that are dominating the field now (GPT-4 and friends), the humble smaller transformers are still quite powerful and have made the problem of translation a somewhat trivial.

My favorite one of these is the T5 network from Google. While large itself, it is capable of being trained using off-the-shelf (though expensive) GPUs. If you can build a large training set, you can train this network at home to accomplish wonders.

Knowing this I set about building a training set that the network could use to learn these ancient languages.

Building the Dataset

Thankfully there has been a push to digitize acquired artifacts and to publish their cuneiform on the web.

The two great projects are the CDLI (Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative) and Oracc. I owe a large debt to these projects.

As any machine learning expert will tell you, 90% of the problem is collecting a good training dataset (the other 10% is justifying the compute bill). Building the cuneiform dataset presented its own unique set of challenges.

Inconsistent Transliterations

Sadly, Assyriologists took some time to settle on a consistent transliteration system. When works were first transliterated to a digital form, only ASCII characters were available and the researchers made due using funny characters like # to denote demonstratives, numbers to disambiguate symbols, and ALL CAPS whenever they were in the mood (just kidding, but the use is so random it might as well be).

When other character encodings became available, researchers adapted. They started to use diacritic marks to disambiguate symbols (loosely based on guessed sounds). And then HTML was invented and they went wild with special marks attempting to better capture the original writing.

While neural networks are powerful and can certainly handle these inconsistencies, it’s not ideal. If you want the network to properly learn the language it’s best not to distract it with also learning the histrionics of human computer interface systems.

A wrote a variety of cuneiform and english normalizers to help with this problem. They’re not perfect, but they do a decent job.

Paragraph Wrapping and Unwrapping

Cuneiform texts are usually written line by line in a column and are read from top to bottom.

These lines are often short and, when translated, contain even fewer words. If I train the network on just these lines (and, surprise, I did for the 1st edition), the translations it produces are also short and choppy. They’re not great.

To work around this problem, I automatically “unwrap” lines into paragraphs to be translated all together. This way the network can learn to translate longer sentences and paragraphs.

The network, however, has its own limitations and can only translate sentences up to 512 tokens long. To work around this problem, I “wrap” the paragraphs into chunks of up to 512 tokens and translate those. I then stitch the translations back together to form the final translation.

This “unwrap” then “wrap” process is not perfect and can lead to some strange translations, but it’s better than the alternative of just translating single lines.

Training Process

I started with a pre-trained a T5 base model from Hugging Face and fine-tuned it on my dataset. This model has 220 million parameters and is capable of translating sequences of up to 512 tokens.

I trained it on a dataset of 210,247 translation examples for 30 epochs. It took about 48 hours on my RTX3090.

While starting with a pre-trained model saves me a lot of compute time, it has drawbacks. The pre-trained model was trained to translate from English to French or German. Ideally, I would have a model that was pre-trained to translate to English.

Also, I used its default tokenizer which does not support all the characters I need and performs poorly on the transliterated cuneiform.

Learning Sumerian and Akkadian Simultaneously

Since my datasets are small in size, I decided to combine learning Sumerian and Akkadian simultaneously. This has the benefit of increasing the training size and exposing the network to more cuneiform symbols. Interestingly, Akkadian often uses some Sumerian intermixed with its own language so it’s not a bad idea to train on both.

Bidirectional Translation

The network was having a hard time converging on a good solution. It would train well enough for many epochs, and then it would fall apart.

I found a regularization strategy that helped a lot. I would train it to also translate from English to Sumerian and Akkadian. Doing this helped the network to always converge. I assume this is an affect of using the pre-trained network.

While translating from English to Akkadian or Sumerian is not a useful task, it is a “fun party trick” as my friend put it.

Future Work

I want to continue to improve the translations and hope to take these steps in the future:

- Fine-tune the model for specific translation tasks like Akkadian to English.

- Pre-train a new model from scratch using a better tokenizer.

- Train a larger model like T5 large.

- Add more training data.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed this deep dive into neural networks and ancient languages.

When I started this project, I had no idea whether it would work or not. I was delighted that it did, and I am extremely delighted to be able to introduce the AICC to the world. Now amateur Assyriologists like myself can read and read to their heart’s content.

Side note: If you are an academic and would like to collaborate on this project, please reach out to me by filing issues on GitHub. I have a million questions about cuneiform that I would love to ask you.